(Click on the photo to download a hi res version for your desktop. It’s Yulais-tastic!)

So, as I promised, here’s the story of my first three days of house visits in Yulias. These visits have several goals: they give me a chance to gather statistical data about how many dwellings have pit latrines, dirt floors, and open fires; as well as an opportunity to talk with each family individually about their needs and the best way we can help them. But a secondary goal is to give us an overall feel for the general poverty level of the village, which I have to say, is a little worse off than our own.

We don’t talk much about fresh water systems, even though they are also part of the project scope, because most people here don’t need them. Springs abound in these mountains, and an international aid organization came through about 15 years ago and built several community water tanks and distribution systems. Still, some are without. Here is one family’s drinking water source we walked past as we were doing our rounds.

We don’t talk much about fresh water systems, even though they are also part of the project scope, because most people here don’t need them. Springs abound in these mountains, and an international aid organization came through about 15 years ago and built several community water tanks and distribution systems. Still, some are without. Here is one family’s drinking water source we walked past as we were doing our rounds.

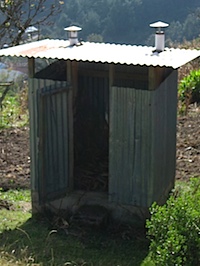

One of our concerns as aid workers is fund misappropriation or project abandonment. In the last few decades, development agencies have come to realize that infrastructure projects must be paired with education, if the people are to know how to use and maintain them. In addition, the modern approach is to ask project recipients to pay a token part of the cost, to encourage ownership. If you give someone something for free, then it has no value to them. As I did my rounds, I saw several classic examples of previous projects gone wrong. Here we see an expensive, sophisticated LASF (composting latrine) that has been abandoned and dismantled for scrap, next to the covered sewage pit the family is now using. Another is a (rather costly) composting latrine that has been converted into a chicken coop, and another that is used to store corn. When I interviewed the owners, some said that they just never liked using them, or they were confused about how to maintain them and wanted training.

To get an idea of what we’re combating, here is a picture of one of the houses I went in. They are cooking their corn for the evening meal, but don’t have a stove (there is a wrecked one in the background). I could only stay in the room for a minute or two before I had to leave. The stoves are nice to reduce deforestation and children getting burned, but the BIG deal is the chimney that takes the smoke out of the house, reducing respiratory damage and subsequent disease. Luckily, many of the families in Yulais already have some kind of stove. Most were handmade a decade ago with adobe, and are really dilapidated with cracks, missing doors, and warped tops that leak smoke. Many of the projects we are looking at are stove replacement jobs. This is a shame in a way, because almost all of the houses still have dirt floors, and the new concrete floors are a big health improvement that is both cheaper and easier to build than the stoves. But it speaks to the Mayan mindset: the dirt floor is what they’re used to, their animals walk around on it just like outside, and they have a tradition of spitting on it/throwing food on it/ washing their hands and mouth out right in the house. Heck, sometimes they even have their kids pee on the floor. To get them to embrace the concrete floor and its related hygiene advantages is a really huge step that most are not ready to make.

Here’s a picture of something that is less common in our area: a mud house with thatched roof. This is one of the poorest families in Yulais. Nas Palas once told me that he grew up in a house like this, and back in those days, no one knew anything else. As time rolls on and people advance, they upgrade to tin roofs, adobe walls, then eventually to block walls, and possibly even concrete roofs (which I hate, but are all the rage right now). But some families get left behind. The funny thing is, this house was actually comfy inside and had a very friendly, wholesome feel. That proves two things to me: “change” doesn’t always equal “improvement”, and someone doesn’t need to spend a lot of money to have a healthy house… they just need to be taught what’s important and what isn’t.

Here’s a picture of something that is less common in our area: a mud house with thatched roof. This is one of the poorest families in Yulais. Nas Palas once told me that he grew up in a house like this, and back in those days, no one knew anything else. As time rolls on and people advance, they upgrade to tin roofs, adobe walls, then eventually to block walls, and possibly even concrete roofs (which I hate, but are all the rage right now). But some families get left behind. The funny thing is, this house was actually comfy inside and had a very friendly, wholesome feel. That proves two things to me: “change” doesn’t always equal “improvement”, and someone doesn’t need to spend a lot of money to have a healthy house… they just need to be taught what’s important and what isn’t.

We then continued into a region new to me: Yulxaq. It literally means “in the hilltops” (yul=in, xaq=hilltop) and it’s aptly named. Here’s a family that I spent a bit of time talking with, since they too invited me in for coffee and a bite to eat. The kids are really nice, and are in fifth and second grades. There were a few more kids not present (herding sheep, most likely) and they all waved to me as we walked away. “Where’s the father today?” I asked Diego as we continued down the trail.

We then continued into a region new to me: Yulxaq. It literally means “in the hilltops” (yul=in, xaq=hilltop) and it’s aptly named. Here’s a family that I spent a bit of time talking with, since they too invited me in for coffee and a bite to eat. The kids are really nice, and are in fifth and second grades. There were a few more kids not present (herding sheep, most likely) and they all waved to me as we walked away. “Where’s the father today?” I asked Diego as we continued down the trail.

“He abandoned them years ago,” he replied matter-of-factly.

Around lunchtime, we stopped in the house of Maricela, one of the teenage girls that translates our health lectures for us. Maricela and her cousin Elisea have been our long-standing allies in doing the work here: they translate, but they also tag along with everything we do in Yulais. They’re a welcome wagon of sorts, always cheerful and enthusiastic. Maricela’s mom is one of the women on the list to receive aid, so I looked at her cracked stove and accepted the offered bread and coffee that happens at every place we go. As we were chatting in the warmth of their kitchen, I asked them what the second project in the house was going to be, since they both live there.

“There isn’t one,” Diego said.

“But the girls come to every lecture! Surely they would be at the top of the list,” I replied. A while back, the villagers decided that the only fair and impartial way to decide who would get aid was to go in the order of who’d attended the most lectures.

The girls shuffled awkwardly a bit. “Well, we decided that if we weren’t on the list, more women could participate, so we opted out,” Maricela explained. I was taken aback; that’s a very selfless and un-Mayan thing to do.

“Since we’re young and don’t have families or houses of our own,” they continued, “it makes more sense for two other women with families to receive aid.” Then they looked at each other and blushed. “We were actually going to ask for something different.” They then explained that they both want to go to a school in town that teaches computer science, so they can get a certification that will allow them to one day get administrative desk jobs. The course costs 100q a month, and lasts 18 months. That’s 1800q each: a LOT of money around here. Was there any way I could help them look for a sponsor, or a scholarship?

They crazy bit is, that’s about $12 a month, or $225 total per girl. That much money can make an amazing difference in someone’s life: the difference between being a young person with a bright future, or a jobless women sitting in a mud house in a cornfield, waiting for the rains to come. I reminded them that I don’t have a salary; the government just gives me enough money to buy groceries. But I promised them I’d put the word out and see what happened. All you readers, you are hereby informed, and if any of you would like to sponsor a young, community-minded Guatemalan teenager please email me and we can talk about it.