After two weeks away on various mandados, it was nice to get back and see how the school is coming along. Normally an architect doesn’t visit a jobsite weekly, but this project is a special case: we’re asking the workers to do something more complicated than they are accustomed to, with foreign drawings, and in a culture where “stuff disappearing” is the norm. I was worried that they’d get ahead of the game, but work slowed down quite a bit while I was away. Semana santa (holy week) last week caused part of the delay; much like the Christmas holidays in the US, no one does much of anything during that time. But a second and possibly more serious concern is that the workers ran out of materials.

As part of the project parameters, Computers for Guatemala (the project sponsor) has decided that the local community will need to go in half on the cost of the material. Don, the director of CFG, is a former Peace Corps volunteer and knows well that if you don’t get the community’s participation this way, the project rapidly degenerates into a handout and creates a dependency on foreign aid. The community’s level of participation is also a way to gauge their general support for the project. Luckily in our case, they are eager to pitch in.

However, due to language and cultural barriers as well as politics, there is some degree of fuzziness about who is going to provide what, and in what quantities. As of today, the masons need (in decreasing order of importance):

- 250+ sacks of cement

- glass block (60, for the windows that let daylight into the lower classrooms)

- gravel/ sand mix

- electrical outlet boxes (30 square and 30 round)

- a truckload of concrete block

- more rebar: 3/8″, 1/2″, and 5/8″

This is interesting, because the gravel is something that Don has told them all along that THEY need to be providing. It’s cheap, locally available, and most of the cost of it is in the labor. I pointed this out to the masons, and they looked at me with their chins in hand. “Hmm, I guess so. OK, we’ll get the gravel. See what you can do about the cement and other stuff, though,” they said. Hey, I’m just the messenger, but I’ll be happy to pass the info along.

This is interesting, because the gravel is something that Don has told them all along that THEY need to be providing. It’s cheap, locally available, and most of the cost of it is in the labor. I pointed this out to the masons, and they looked at me with their chins in hand. “Hmm, I guess so. OK, we’ll get the gravel. See what you can do about the cement and other stuff, though,” they said. Hey, I’m just the messenger, but I’ll be happy to pass the info along.

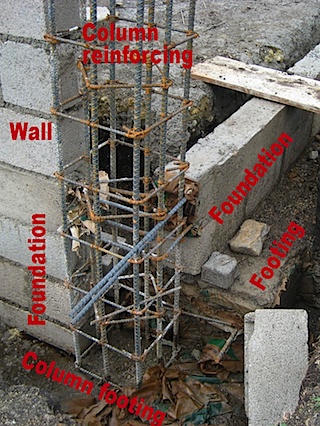

After we got that stuff out of the way, I looked at their work so far. They’ve brought the walls up above grade level on the south wing, and have poured the bottom half of some of the main columns. I was pleased to see a lack of honeycombing and voids on the concrete, which means that they have been agitating during the pour, as I instructed. They have also been bending hooks on the rebar in all the joints, which is good construction practice. The walls looked planar and true, another sign of quality work.

Sometimes, though, the economy of Guatemala prevents the sort of quality I’d like. Here we see a mason cutting a block in half to fit into the remaining space in the wall. They do it here by chopping it with a hatchet. This is prohibited on work in the US, as it weakens the block, but no one here has a block cutting saw… and everyone has a hatchet.

Most of the other “irregularities” I saw were a result of differences in the traditional techniques of construction. In the US, for example, in concrete block walls we reinforce them buy placing a rebar of a calculated size in cores at a calculated spacing, and grouting them solid. In Guatemala, they build their block walls without reinforcing in the cores, but leave a half-block-wide space every two meters. In this space, they put four #5 rebar with #3 stirrups every 8 inches. They then place boards on either side of the wall as formwork, and concrete the steel in place like mini columns. Every 5 courses, they do the same thing horizontally as well. The end result is a reinforced concrete grid with block infill, except the block happened first. I see it EVERYWHERE, so it must empirically withstand most forces incurred by small scale masonry construction. My guess is that after the big quake in ’76, some international team of engineers came in, looked at the construction loads in 99.5% of the buildings, and said, “You need to do THIS instead of adobe, if you want to not be crushed to death in your sleep by an earthquake.”

Most of the other “irregularities” I saw were a result of differences in the traditional techniques of construction. In the US, for example, in concrete block walls we reinforce them buy placing a rebar of a calculated size in cores at a calculated spacing, and grouting them solid. In Guatemala, they build their block walls without reinforcing in the cores, but leave a half-block-wide space every two meters. In this space, they put four #5 rebar with #3 stirrups every 8 inches. They then place boards on either side of the wall as formwork, and concrete the steel in place like mini columns. Every 5 courses, they do the same thing horizontally as well. The end result is a reinforced concrete grid with block infill, except the block happened first. I see it EVERYWHERE, so it must empirically withstand most forces incurred by small scale masonry construction. My guess is that after the big quake in ’76, some international team of engineers came in, looked at the construction loads in 99.5% of the buildings, and said, “You need to do THIS instead of adobe, if you want to not be crushed to death in your sleep by an earthquake.”

A few quick notes:

Don and Computers for Guatemala have released a new website specifically for the school project, to help with promotion and fundraising. Click here to check it out. If you click on the Naming Opportunities tab, you can see what each room costs, if you want to get your name on a classroom in Guatemala.

There is a new functionality in my blog interface as well. At the sidebar on the right, you can click “The Mayan School index” under Links to get just the blog entries about this project, and no others. Try it; you’ll like it.