As you may remember, we’ve been working on getting a SPA project for Yulais, a neighboring village, for a long time. In essence, the idea is that we work with the village leaders to solicit grant money to help the people build health-improving infrastructure in their homes: things like concrete floors to replace mud, stoves with chimneys to replace open fires on the floor, latrines instead of pooping in the field. To receive the projects, the villagers have to attend our health training seminars, as well as kick in a portion of the money and/ or labor for their individual project.

After more than a year of meetings, paperwork, planning, interviews, audiences with the mayor, and so forth, we finally received word a few weeks ago that we’d been approved by USAID, a branch of the US government that deals with third-world development and gives grants for this sort of thing. It was a happy day, the culmination of a lot of work and frustration. I have to hand it to the Yulais leaders; they gave it their all to cope with a very alien concept and jump through the multiple hoops set up by our federal government. They did things that they would never have imagined doing before- filling out forms on a computer, opening a community bank account (that took MONTHS), and organizing the villagers to work together for a common goal.

After all that, it was a pleasure to meet with the leaders last week to explain our success. “Congratulations,” I said. “We just received word that your community account has been credited a bit over 29,000 quetzales.” Smiles all around; happy day. “I have here a form with the names of all the participants in the village, and the project type they said they wanted.” Hand shaking, nodding. “On this column after the project type, is shows the cash contribution each family needs to make to match the grant. I can’t wait to start!”

It was like in the movies, when you hear that record scratching noise and all conversation stops.

As Emily said after the meeting, Diego (the speaker for the committee) looked as though he’d been punched in the gut. “Um, that’s a lot of money,” he said after a pause. Some fast discussion ensued, and it became apparent that despite our saying it repeatedly for months, no one really realized that they’d have to spend THEIR OWN MONEY to get some nice stuff from Uncle Sam. I mean, they heard us say it, but just didn’t get it. Or believe it. Or think we weren’t joking.

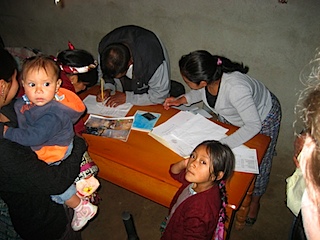

We all discussed the situation, and set up a meeting to explain it all to the participating families a few days later. The families all filed in, and we explained everything again. At first, they were all excited to look at the drawings of how we are going to build the project. But their excitement soon changed to sticker shock as well. The meeting drug on for hours, and we eventually dispersed so that each woman could go home and talk it over with her husband.

We all discussed the situation, and set up a meeting to explain it all to the participating families a few days later. The families all filed in, and we explained everything again. At first, they were all excited to look at the drawings of how we are going to build the project. But their excitement soon changed to sticker shock as well. The meeting drug on for hours, and we eventually dispersed so that each woman could go home and talk it over with her husband.

Afterwards, we got on the phone and called some other volunteers. Several of them said that they were able to work their grants so their villagers paid little to nothing, except for pitching in all the labor. One volunteer just did half as many families; another got a huge donation from her hometown church to put more money in the bank. Now we are second guessing ourselves… did we royally mess this up?

The grant is for a fixed amount of money, so the more families that participate, the higher the amount each will have to pay. I can’t make the price of the materials go any lower; I got signed quotes from three different vendors. After the meeting, we toyed with the idea of calling people in the US to look for more money to supplement the grant… but where do you stop? I am against the idea of giving stuff away for free; that sort of paternalistic gift fosters dependency and promotes a welfare state. Is 600q really too much to ask someone? Yeah, yeah, i know they’re poor. It’s true. But put it in perspective: 600q is 20 days labor, but for that they get a major improvement to their home. How many days wages would you have to save if you wanted to add a new bathroom to your house? Also, they all receive Mi Familia Progresa, the local equivalent of a welfare check, every month. 600q is two months of welfare. Welfare that they did fine without, last year before the program started, and will have to do without again when the current president leaves office in 2012. We explain to them that it might make more sense to spend that money on a nice new floor or a stove that will be serving their family for the next few decades, instead of a lot of Coke and chips and DVDs, or a stereo system that will be broken in a few years. That is what most of them spend the money on right now.

The thing is, oftentimes when you build something, the client wants to get a bunch of cool stuff but doesn’t want to pay what it’s worth. They think there should be some better deal, or that you can somehow make it cheaper. But every architect knows that if you want it cheaper, you can either reduce scope or quality, and after more than a decade of that fight, I tire of the game. If they don’t want to pay, I can’t squirt out my own blood to make it cheaper. So some of them will just have to do without, and I will get on with business. Emily is less jaded and more amiable, so was feeling pretty ill about halfway through the meeting. “I know you’re used to this,” she said, “But I hate it. I just want to get to the part where we’re building stuff and everyone is smiling.”

Well said! I second that notion, and despite my “jadedness”, this whole situation gets me down too. Who I REALLY feel sorry for in all this is Diego; he has worked on this project thanklessly for months, only to get accused of tricking his friends and neighbors. We get to go home in three months; he has to live in Yulais forever.

When all was said and done, a third of our families dropped out of the project tonight. We expect that the number will drop further, because some are surely hedging their bets, waiting for us to re-allot the remaining money to lower the contribution for those who are left. Tonight I have to crunch the new numbers to see how the grant will split up over 30 families instead of the original 44, and tomorrow we have to have yet another meeting with all the participating families to try to sort this all out. One of the parts that really sucks and breaks my heart is that a few of the families that dropped out were REALLY needy and participatory, great candidates for this sort of aid.

This is a good example of how Peace Corps is hard. That superficial stuff like pooping in a pit and washing your dishes in a stream is more dramatic, true. But trying to get abysmally poor, uneducated people to lift themselves out of their situation while they are inadvertently kicking and screaming against all your help? That part is like trying to move a mountain.