We are back from the jungle, and what a trip it was. Much like last year’s Holy Week, this one was a great opportunity to see more of what Guatemala is all about. But in this case, it was all about natural wonders and ancient Mayan prehistory instead of religious festivities and colonial Spanish architecture. So much happened that we’ve decided to jointly write this post, much like last year’s adventure.

Guatemala is full of ancient Mayan ruins, the most famous of which is Tikal, a Mayan city that flourished from about 300AD on. It’s located in the center of the Peten, a steamy low-lying jungle that is the northernmost panhandle of Guatemala. But soon after our arrival, we learned that there are hundreds of other ruins, and archaeologists estimate that they’ve located less than a quarter of what’s really out there beneath the jungle. Some are simple, small, and easy to get to, like Zacaleu, Ixtatán, or Iximché. They are relatively recent, dating from 1000AD to 1500AD, and are easy to find because they are located in or near cities that are still occupied by present-day Maya. Others, however, are more elusive. The vast jungle north of Tikal holds a plethora of ruins, the most famous of which is El Mirador.

We heard about El Mirador soon after we arrived in Guatemala, and decided almost immediately that we needed to see it before we left. It was only discovered a few decades ago, and is largely buried by trees and vines. Archaeology work continues, but at a slow pace: access is by a two-day jungle trek with pack mules (or by helicopter)… and that only after you’ve made the tough journey into the Peten. That challenge itself was enough to grab our interest, but El Mirador has other noteworthy distinctions as well. Many of the pyramids predate Christ by 200 years, a full half millennium before Tikal; and the largest pyramid, La Danta (“the Tapir”), is bigger by volume than any of the Egyptian pyramids. El Mirador was the cultural and economic center of Central America for centuries, with highways stretching out to cities in every direction. It’s amazing how much we know about ancient Rome, but how little about classical Mayan civilization, its equal on the other side of the planet.

Travel of any substantial length in Guatemala involves mishaps, and this was no exception. Our original plan was to take the overnight bus from Guatemala City to Flores. We arrived at the bus station in Guatemala City at about 5pm, only to discover that our seat reservation, which Charlotte had confirmed several times, had been lost and the bus company staff was completely unapologetic about having given our seats away. This very Guatemalan outcome was a fortunate mistake; we ended up taking a taxi to a different bus line a few blocks away, where we found seats on a much nicer bus (AC and a bathroom!), if we could wait until 11pm to depart. Guatemala is all about waiting, so we got out the cards and settled down in the terminal. We were, for a time, very amused by the red glowing toilet in the ladies room. Some unfortunate lady’s phone apparently slipped from her pocket and into the bowl. The red glow was eerie upon walking into the dark bathroom, but hilarious once we figured it out. You should have seen the Guatemalans staring at the weird gringos who kept walking in and out of the bathroom in turns, laughing hysterically. We didn’t think to alert anyone to the situation, and after we were all focused on our card game, a local woman and her daughter walked into the dark bathroom and squealed. Hilarious! They did alert the bus station attendant, who couldn’t find anything with which to extract the phone. Finally a local man who looked ready to start his vacation (white sox with brown leather sandals) reached in and pulled it out.

With our departure pushed back, our new arrival time in Flores was set for about 8am. This later schedule proved handy when the bus ran out of gas, just after sunup. “You’d think that if his JOB were to drive the bus, the least he could do was make sure there was enough gas in it,” Charlotte grumbled as we stood around at the side of the road, blinking in the early morning sun. When she’d first asked him what the problem was, he told her, “oh, es solo un pequeno error.” (Oh, it’s just a little mistake.) But these things happen, especially here, and about twenty minutes later, another bus came by and a guy got off carrying a 5-gallon bucket filled to the rim with sloshing diesel fuel. Watching that chubby old driver sweating and struggling with pouring a huge bucket into a fuel filler at shoulder height made it all worth it.

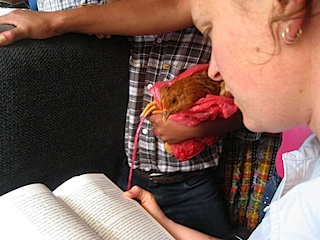

I’d like to say that we had better luck on the way back, but we didn’t. Just different. The return bus was an old broken down Greyhound from the 80s, and the route wasn’t a first-class route. That saved us about 40Q each ($5), but meant that it stopped every ten minutes to pick up people, adding several hours to an already painfully long journey. And since the seats were filled when we left the station, all the newcomers had to stand in the aisles. Or, that was the idea. In reality, they leaned over the paying customers or pretended to “accidentally” sit on their laps. At one point, a kid was holding his poopy chicken right over Emily and the book she was reading. Luckily, the book was interesting and kept the chicken’s attention long enough to prevent any mishaps.

I was pretty excited that we’d get to spend some time in the city of Flores. While visiting Tikal with The Four Witches back in September, I’d read up on the city and really wanted to see it. It just worked out that our in-park rooms near the ruins and nearer still to a cool shimmering pool made the trip to Flores seem too long, too hot, too far away, and not nearly as enjoyable as the shaded corner of the pool or shaded porch of our thatched rooms. In fact, we were expecting a pretty arduous journey into the Peten based on the temperatures we experienced in September. Fortunately, the weather had mercy on us. Don’t get me wrong; it was definitely hot, but not nearly as hot as our first visit. A little behind schedule, our big red bus rambled over the bridge that connects the town of Santa Elena with Flores, a tiny island community in the center of Lake Peten-Itzá. Just the fact that we were on a little island made things feel a bit exotic. Because we’d managed to get the last seats on the 11pm bus, we were in the back seats which do not recline. Though we tried to take turns lounging across one another (at least Charlotte, Sara, and I all took turns), we didn’t sleep a whole lot, but the new scenery woke me up a bit and the prospect of a tasty breakfast kept me going. Guided by the more experienced ones in our group, we were led to Casa de los Amigos, serving up plenty of tasty treats. We all commenced to eat heartily. I felt like our vacation had properly begun.

I was pretty excited that we’d get to spend some time in the city of Flores. While visiting Tikal with The Four Witches back in September, I’d read up on the city and really wanted to see it. It just worked out that our in-park rooms near the ruins and nearer still to a cool shimmering pool made the trip to Flores seem too long, too hot, too far away, and not nearly as enjoyable as the shaded corner of the pool or shaded porch of our thatched rooms. In fact, we were expecting a pretty arduous journey into the Peten based on the temperatures we experienced in September. Fortunately, the weather had mercy on us. Don’t get me wrong; it was definitely hot, but not nearly as hot as our first visit. A little behind schedule, our big red bus rambled over the bridge that connects the town of Santa Elena with Flores, a tiny island community in the center of Lake Peten-Itzá. Just the fact that we were on a little island made things feel a bit exotic. Because we’d managed to get the last seats on the 11pm bus, we were in the back seats which do not recline. Though we tried to take turns lounging across one another (at least Charlotte, Sara, and I all took turns), we didn’t sleep a whole lot, but the new scenery woke me up a bit and the prospect of a tasty breakfast kept me going. Guided by the more experienced ones in our group, we were led to Casa de los Amigos, serving up plenty of tasty treats. We all commenced to eat heartily. I felt like our vacation had properly begun.

At first, we thought it unfortunate that this same hostal didn’t have room for us (they don’t take reservations), but it turns out Alana, the first of our group to arrive, had found a great little hotel that offered clean, spartan rooms with private bathrooms. The best part, though, were the fans in each room and rooftop hammocks to enjoy the breeze and views of the lake. After eating, we moved into our hotel, showered, and hung around in the hammocks soaking up the warm breeze and pleasant views. Lake Peten-Itzá is Guatemala’s third largest, following Izabál on the east coast and Atitlán in south central Guetemala. The tiny town feels about 4 blocks wide in each direction, and while the building construction and bright colors seemed familiar, Flores felt a little different than typical Guatemala. The island was originally settled by Mayans that had migrated south from Mexico. The settlement was largely ignored by the Spaniards until late in the Conquest, and was therefore the last independent Mayan settlement before they got wiped out in 1697.

We used Flores as fueling station, filling up on food and catching up on rest before setting out on our epic adventure. It served us well in this respect, and we enjoyed the quiet streets and pleasant sunset. On our way out to dinner we ran into this giant dead tarantula squashed in the street. Thankfully, this was the only one we saw during the trip. Sunday we had half the day to relax and eat before our microbus showed up to take us grocery shopping and deliver the eight of us on the dusty dirt road to the tiny community of Carmelita, located three and a half hours away in the Mayan Biosphere National Reserve.

I got the name of Doña Pati from some PCVs who had done the trip before, so I called her and set up the reservations for all of us. When we’d begun to look into a trip to El Mirador, we’d heard prices between $250 and $400. None of us could afford this, but going straight to the tour guides in Carmelita instead of working through a tourist agency in Flores brought down the cost quite a bit. Most of our group elected to bring our own food and tents, which also helped. If you include what we paid for transport there and back (8 of us renting a van) and the food we bought for ourselves, the trip was quite a deal at about $100/ea. Little did we know what a bargain we were in for.

I got the name of Doña Pati from some PCVs who had done the trip before, so I called her and set up the reservations for all of us. When we’d begun to look into a trip to El Mirador, we’d heard prices between $250 and $400. None of us could afford this, but going straight to the tour guides in Carmelita instead of working through a tourist agency in Flores brought down the cost quite a bit. Most of our group elected to bring our own food and tents, which also helped. If you include what we paid for transport there and back (8 of us renting a van) and the food we bought for ourselves, the trip was quite a deal at about $100/ea. Little did we know what a bargain we were in for.

We arrived in tiny, quiet Carmelita around 4:00 in the afternoon. It felt more like a scene from Africa than the Guatemala to which I’ve grown accustomed; tiny huts with thatched roofs made a semi-circle around the perimeter of the town, backed by jungle wilderness. Pati had informed me that we were welcome to spend Sunday night in her backyard in Carmelita for no extra charge, and as a group we decided this was excellent. It turns out she and her husband, our guide Carlos, had invested much of their earnings into setting up a small campground with latrines and a shower area (bucket bath only, but WAY better than nothing).

Pati saw that we were all settled and said her good byes for the night, adding, “You might want to put your tents in under the porch. It looks like it’s going to rain.” A few people expressed some skepticism at this remark. Lesson: on matters of weather, you should trust the locals. The rain started shortly after sundown, but it brought cool wind and nice weather for sleeping. We got up early the next morning, and after the guides had loaded up the mules, we were on the trail by nine. Although we were under a light drizzle, I felt generally relieved we weren’t walking through sweltering heat. Everyone seemed in high spirits, and we were off!

Our guide Carlos was a calm, friendly guy. I got to chat with him on several occasions, and learn about his life and family and work. He has some crops planted, but most of his living is from guiding tourists and renting mules to other guides for their work. He told me proudly that he has over 20 mules. “How much does a mule cost?” I asked.

“About five or six thousand,” he said. “But it’s really more than that, because I have to pay the vet to come out every now and then to give them shots and check up on them.” Wow, that is a huge investment for a Guatemalan. About that time, we passed by a tomb that had a tunnel cut out of the side of it by grave robbers. We’d seen a few of those before, so I asked him about it.

“It used to be that people came to steal the offerings, to sell to antique traders,” he explained. “People need to make a living, get enough to eat. That doesn’t go on so much anymore, now that we have tourists like you, and the people can guide or lead mules. It all changed about 20 years ago. Now the only robbers are the Mexicans that come across the border to steal the treasures, but that is slowing down too, because now the government posts more guards on the site.” The Mexican border is pretty close to El Mirador, only about 6km away.

President Colom and others in the Guatemalan government are contemplating putting a rail line in from Carmelita out to the ruins. That would change everything so dramatically. It would change the tiny community of Carmelita, as well as the feel and level of development inside the park. I think El Mirador is a treasure to the world, but I also like the present challenge of really having to work to get there (or pay the right price). However, I’m sure over time, access will change and the traffic will increase. I found myself worrying that those who work in and around Tikal might suffer as tourist traffic skips little Tikal, and goes right to the world’s giant. But I will admit, I felt a bit smug after a while. We can tell our great nieces and nephews or anyone silly enough to sit and listen to old fogey ramblings that we walked to El Mirador before the train was there, before things were again so set in stone (literally) and programmed. This did feel like a pretty “epic” trip, as we all jokingly dubbed it in the planning phase. My niece at home will definitely term this as another one of “Aunt Emmy’s aVentures”.

President Colom and others in the Guatemalan government are contemplating putting a rail line in from Carmelita out to the ruins. That would change everything so dramatically. It would change the tiny community of Carmelita, as well as the feel and level of development inside the park. I think El Mirador is a treasure to the world, but I also like the present challenge of really having to work to get there (or pay the right price). However, I’m sure over time, access will change and the traffic will increase. I found myself worrying that those who work in and around Tikal might suffer as tourist traffic skips little Tikal, and goes right to the world’s giant. But I will admit, I felt a bit smug after a while. We can tell our great nieces and nephews or anyone silly enough to sit and listen to old fogey ramblings that we walked to El Mirador before the train was there, before things were again so set in stone (literally) and programmed. This did feel like a pretty “epic” trip, as we all jokingly dubbed it in the planning phase. My niece at home will definitely term this as another one of “Aunt Emmy’s aVentures”.

One of the things I like about El Mirador and the surrounding area is that it’s a fantastically huge expanse of preserved wilderness, much like a national park in the US. That means it doesn’t have many of the downers of Guatemala: noisy busses, blaring music, aggressive salesmen. You can even pitch your tent and sleep under the starts without worry of being robbed. This is not to say that it’s perfect; the Peten region has its share of narcotraffickers, illegal logging, and related murders in both industries. But as Carlos explained, the narcos and the tourist guides know where each other frequents and stay out of each others’ way, as it’s mutually better for business.

There wasn’t as much wildlife as I’d expected, considering it’s a jungle. After the tarantula scare in Flores, we saw very few bugs. No big cats, either… the dry season is hard on the jaguars and they hunt elsewhere. The toucans and jungle turkeys were there, a few coatis, and a fox; as well as the monkeys (both howler and spider). We didn’t see much of the howlers, we just heard them at night, roaring away like King Kong. Our first night at El Mirador, shortly after we’d all bedded down and things had fallen silent, the howlers started up, and got closer and closer. It felt like they had to be in the trees just above us. It was crazy and cool. Then I put my earplugs in and feel asleep. I’m glad they found no need to descend from the trees and investigate those who’d invaded their territory. It would be pretty terrifying if you didn’t know what it was, and Emily got a great audio clip at sunrise for your enjoyment. The spider monkeys were more visible, though, swinging in trees and watching us with mild disinterest. Sometimes they did get interactive, though, like this monkey who decided he didn’t like us in his territory. He grabbed branches with all four hands and shook them like crazy, to try to intimidate us. We thought it was cool, so we hung around to take a video. He was not amused, and took to snapping off branches and throwing them at us. His aim got better on the next throw, and I had to dodge at the last second. Check it out: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=loaCcsycerI

But the most exciting wildlife we saw was the barba amarilla, or yellow-bearded snake. I came hiking up the trail one afternoon and Anne was standing there, staring at the ground.

Anne had been paranoid about snakes the whole trip, ever since our boss told her that the jungle was teeming with poisonous vipers of all kinds. So far, we’d seen none, but I looked past her to see a tiny coiled snake in the middle of the path.

“Huh,” I said, bending over to get a picture. About that time Carlos came up behind me, leading his mule.

“Is that a rattlesnake?” Anne asked him.

He peeked, and shook his head. “No, that’s barba armarilla. Far more poisonous than cascabela (rattlesnake). Be very careful,” he said with caution. “Do you want me to kill it?”

Anne frowned. She’s not a big fan of killing things, and she told him so.

“Well, if we leave it, it might kill one of my mules,” Carlos warned. “A bite from that thing, and a mule will be dead within an hour.”

Hearing that, we all backed away an extra step, and Carlos took out his machete. I was sortof expecting an Indiana Jones type battle to ensue, but instead Carlos went to a nearby tree and cut himself a stick that was about 8 feet long and as big around as my thumb. “It’s very dangerous to attack them with a machete,” he explained. “It puts your had too close to where they can strike.”

Hearing that, we all backed away an extra step, and Carlos took out his machete. I was sortof expecting an Indiana Jones type battle to ensue, but instead Carlos went to a nearby tree and cut himself a stick that was about 8 feet long and as big around as my thumb. “It’s very dangerous to attack them with a machete,” he explained. “It puts your had too close to where they can strike.”

WHACK! WHACK! WHACK!

With three quick whacks of the long stick, the snake was very decisively pummeled to death. He lifted it with the stick and hung it in a tree, and we were once again on our way. “No, you go ahead,” Anne told me, stepping to the side of the path and smiling.

Carlos informed us at this point that he always carries antidote to the barba amarillo with him on these hikes. While the mule would die within in an hour, a man would die in two (slower heart rate), but with the antivenom and the possibility to call for a helicopter, there’s a chance a man could survive. Again, we were all pleased with Carlos and his preparedness.

FIRST DAY: EL TINTAL

We really lucked out on the weather. The mercury never passed the 90s, a rarity for the Peten. We had planned the trip for the dry season, which was a boon on many counts. The dry earth kept the bugs to a minimum, and it was possible to hike free of mud. Our guide told us that they still work in the rainy season, but everyone rides the mules because the mud is halfway up your thigh. Yikes. Carlos told us how he’s lost more than one mule to drowning, and just for the fun of it he led us across the makeshift “bridges” over the deepest ravines. I can’t imagine how treacherous it would feel to cross these lashed together logs while they’re wet and slippery, with water rushing below your feet.

We really lucked out on the weather. The mercury never passed the 90s, a rarity for the Peten. We had planned the trip for the dry season, which was a boon on many counts. The dry earth kept the bugs to a minimum, and it was possible to hike free of mud. Our guide told us that they still work in the rainy season, but everyone rides the mules because the mud is halfway up your thigh. Yikes. Carlos told us how he’s lost more than one mule to drowning, and just for the fun of it he led us across the makeshift “bridges” over the deepest ravines. I can’t imagine how treacherous it would feel to cross these lashed together logs while they’re wet and slippery, with water rushing below your feet.

Speaking of water, during the dry season there isn’t any. Much of the mules’ loads were jerrycans of water, about 5 gallons for each of us. Carlos told me that before he was a guide, he was a laborer at the archaeological site. He got paid 100q a day ($12, a kingly wage around here) to haul water ten miles each way on his back for the archaeologists, 12+ hours a day. He said it was awful work, and he would like to never do it again. The dry season doesn’t just affect archaeologists and hikers; the jaguars don’t hang around the park during that time and the snakes don’t come out much either. We got drinking water as part of the cost of the trip, but if we wanted to bathe in a bucket, we had to pay a guy 10q for some unfiltered brownish water to splash on ourselves. Which we gladly did. Some look at the glass and say it’s half empty. Some say it’s half full. A Peace Corps Volunteer asks, “Hey can I take a bath in that?”

The first evening we camped at El Tintal, a recently discovered ruin that hasn’t even been excavated yet. It is the remains of a pretty big city-temple complex, with a sophisticated moat system that is still evident if you know what you are looking at. It’s on the saqbe’, or ancient Mayan highway, that runs from Tikal up to El Mirador. We left our gear and mules at the base camp (a collection of straw roofs and a fireplace) and went exploring with Carlos. He took us up El Tigre, a temple that he and another guide discovered some 20 years ago. “He’s dead now,” Carlos explained. “He was an older man, and had been a guide for a long time.” He didn’t speak much more about it, but I got the impression that they were friends, or maybe this other fellow was Carlos’s mentor.

From atop El Tigre, we could see an amazing view of the jungle canopy, complete with monkeys foraging for their evening meal. “If you look over there at the horizon,” Carlos showed us, “you can see El Mirador.” It was a green ridge in the distance, and it looked like a lot of jungle between here and there. We could also see another ruin off to the east, a bump of trees protruding from the canopy. It was the temples of Nakb’e, a ruin even more recently discovered than the ones we were standing one, that Carlos also claimed to have part in finding. We weren’t aware it was an option, but if we’d planned a six day excursion, we could have walked a triangle from Carmelita to Tintal, Tintal to El Mirador, El Mirador to Nakb’e, then Nakb’e to Carmelita. It was a shame to have passed it up, but we saw lots of cool stuff anyway. If you’re looking in to doing this trip, be advised that it would be a worthwhile option.

From atop El Tigre, we could see an amazing view of the jungle canopy, complete with monkeys foraging for their evening meal. “If you look over there at the horizon,” Carlos showed us, “you can see El Mirador.” It was a green ridge in the distance, and it looked like a lot of jungle between here and there. We could also see another ruin off to the east, a bump of trees protruding from the canopy. It was the temples of Nakb’e, a ruin even more recently discovered than the ones we were standing one, that Carlos also claimed to have part in finding. We weren’t aware it was an option, but if we’d planned a six day excursion, we could have walked a triangle from Carmelita to Tintal, Tintal to El Mirador, El Mirador to Nakb’e, then Nakb’e to Carmelita. It was a shame to have passed it up, but we saw lots of cool stuff anyway. If you’re looking in to doing this trip, be advised that it would be a worthwhile option.

We didn’t run into many other hikers, but the ones we did meet were friendly. The first evening, we met a pair of Peace Corps volunteers from Honduras who were on vacation with their buddy, a yoga instructor. We returned from El Tigre ruin to find them practicing in the campsite. Oh, wait, did I say yoga? Sorry, turns out they do acro-yoga. We’d never heard of that before, so we sat staring at them, mouths open, until they noticed and invited us to join them. Emily and I once did acrobatic swing dancing, and we do yoga now, so we were totally game to give it a try. I am pleased to announce that we didn’t dislocate anything in the attempt, and will start looking for an acro-yoga studio when we return to the US. It was pretty much super fun and the stretching it provided was much appreciated after our first day of hiking.

Although most of us brought our own food to save cost, Nic and Katie shelled out an extra 250q (about $30) each to avoid the hassle. Who’d have guessed that for the money, you also got a muchacha to COOK the food? Her name was Maribel, and she was very friendly and a quick hand with the frying pan. The first morning in Tintal, she was very worried about those of us who had brought our own food. “Are you sure you don’t want me to fix you something? You have a lot of walking to do today. You’re going to need the energy. I have some extra beans and potatoes if you want it.” In spite of being around our age, she was like a mother hen. We went about making our bowls of loaded oatmeal, with tons of nuts and dried fruit. Maribel was not convinced this would get us through until lunch, and shook her head disapprovingly as we ate. When we were eating oatmeal and ramen noodes, Nic and Katie were having homecooked candlelight dinners, the last of which was broiled chicken. How do you get uncooked chicken to not spoil on a 5-day jungle trek? Easy… you don’t kill it until you want to eat it. On our last day hiking out of the jungle, I saw a larger group pass on their way into the ruins. There were three chickens strapped in make-shift holsters, like chicken straight jackets, to the side of a couple of mules. It was hilarious, but I wasn’t quick enough with the camera to get the picture for you. You’ll just have to imagine. [A note to my mother–notice the travel french press in use for puffy-faced me in the morning. Thanks ma!]

Maribel’s presence was actually a boon for all of us, and we owe Nic and Katie a favor for hiring her. She shared hot water with everyone, and was the source of occasional goodness like the time we stopped for a break in the sweltering heat and she busted out a watermelon from somewhere amongst the mules. That was the moment I realized that I had to tip big when we got back. And did I mention, the mules were a good thing too? I sure wouldn’t want to hike for five days with a ten-pound watermelon in my backpack. I wouldn’t have wanted to start out the trip like the mules, carrying five gallons of water per person. But I was glad to have it, since we all averaged about 3 litres a day just for drinking.

Sadly, no one told us about the option to buy bathing water this first night. We went to bed sticky with sweat from the days walk, and in the middle of the night the wind whipped up and chilled most of us. Fletch and I were only mildly uncomfortable, but a few people were miserable. When the first of us woke up a little before six, the fire had been lit for hours and our pot of water boiled to make food. Carlos was up and poking the fire; he sleeps in a hammock under the shelters and said it was so cold he couldn’t stand to stay in bed after about 3am. That’s something we weren’t expecting: weather in the jungle cold enough to see your breath!

SECOND AND THIRD DAY: EL MIRADOR

As I might have mentioned before, El Mirador is an active archaeological site. For several months out of the year, it’s swarming with workers and researchers and students- none of whom were present this week. The dry season makes work essentially impossible right now, due to lack of drinking water, so they only show up during the rains. Conveniently the rains in May, June, and July correspond with when University folks can make it down from the US to work on the project. Unfortunately for them, that means they get to work with mosquitos and foot rot and soggy clothes and 100% humidity, whereas we had a pleasant little jaunt in the woods. Carlos took us around to see some of the work areas that the archaeologists use: storage buildings for ceramics shards, washing stands for cleaning artifacts, tents for the researchers, and a screened-in building where they set up their computers. We also saw two gorgeous bungalows that are occupied by the park and project directors while they are in residence.

As I might have mentioned before, El Mirador is an active archaeological site. For several months out of the year, it’s swarming with workers and researchers and students- none of whom were present this week. The dry season makes work essentially impossible right now, due to lack of drinking water, so they only show up during the rains. Conveniently the rains in May, June, and July correspond with when University folks can make it down from the US to work on the project. Unfortunately for them, that means they get to work with mosquitos and foot rot and soggy clothes and 100% humidity, whereas we had a pleasant little jaunt in the woods. Carlos took us around to see some of the work areas that the archaeologists use: storage buildings for ceramics shards, washing stands for cleaning artifacts, tents for the researchers, and a screened-in building where they set up their computers. We also saw two gorgeous bungalows that are occupied by the park and project directors while they are in residence.

But the main point of the trip was the ruins themselves. I can’t really do them justice with words, so I will let the pictures do the talking. El Mirador is a massive, ancient Mayan city filled with temples and passageways, giant leering faces and lofty terraced plazas.

We hiked with gusto for two days to get into the park. Once we arrived, we got to take all the time we wanted that afternoon and the next day for resting at the campsite and visiting all the ruins. By this point we’d all taken a liking to Carlos, so whenever we sat down to take breaks and pulled out granola bars, dried fruit, and nuts, we’d collect some from all of us and pass it over to Carlos. On Wednesday we were sitting around camp snacking in the afternoon as he strolled in and laughed, “You guys have so much food! Like it comes out of nowhere.” He went on to explain that while he and Pati were separating cargo and loading the mules right before we started, they’d come to the conclusion that the six of us who said we’d bring our own food had come woefully unprepared. Pati, saying nothing to any of us nor adding any additional charge, had packed surplus food for our cook, Maribel. I think she was under instruction to pressure us to eat adequately. We all now understood Maribel’s concern, and laughed with Carlos. This was just another way we found them to be a very considerate touring outfit.

There were lots of great things about this trip. The group couldn’t have been better. Being out in the woods and hearing only nature do its thing for five days! No regatone, no honking chicken buses, no screaming kids. But I think what I loved the most was the feeling that we were somewhere with so much possibility. It feels like a National Park waiting to happen. The land is already a protected area/national park, but there’s none of the other stuff…hotels, swimming pools, tourist shops, kids attacking you to shine your shoes, even if you’re just wearing sandals and they’d be blacking your feet. There are some folks who come in by helicopter, like President Colom and Mel Gibson. The latter visited to glean inspiration for his film Apocalypto, which I have not seen but now feel I must when I resume my Netflix subscription, in spite of being told it’s a terrible film. The ‘copter ride is just $400 (witches, you would dig this place, but I think you’d enjoy the helicopter ride in and out rather than the five day trek). Anyway, this absence of traffic was cool and maybe a little eerie. The feeling of solitude was magnified by all the archaeology work stations in pause, all their dormitories and offices abandoned. The ruins are so raw, half uncovered. You feel like you’re standing on so much waiting to be discovered. Who knows what information they’ll have twenty or thirty years from now?

I also found it difficult, after a few days of just enjoying walking in the woods and appreciating nature, to really comprehend that what we were seeing at El Mirador (and a few stops along the way) were all man made, not nature made. To imagine whole societies and cultures existing and thriving here in a place the present-day archaeologists find uninhabitable for much of the year is pretty interesting. We spent each sunset atop a temple, and the morning we left the park, Charlotte, Sara, Anne, and I pulled ourselves out of bed to go with the ever-patient Carlos to sit atop a temple and watch the sun come up to the sound of howler monkeys in the distance and a breeze stirring the canopy. Many current theories propose that different indigenous groups left their cities (including the Anasazi [1] cliff dwellers in the U.S southwest) for reasons of environmental degradation: the masses of people could no longer support themselves on the available land. It’s fascinating, maybe also a little discouraging, that we humans are still what we have always been.

I also found it difficult, after a few days of just enjoying walking in the woods and appreciating nature, to really comprehend that what we were seeing at El Mirador (and a few stops along the way) were all man made, not nature made. To imagine whole societies and cultures existing and thriving here in a place the present-day archaeologists find uninhabitable for much of the year is pretty interesting. We spent each sunset atop a temple, and the morning we left the park, Charlotte, Sara, Anne, and I pulled ourselves out of bed to go with the ever-patient Carlos to sit atop a temple and watch the sun come up to the sound of howler monkeys in the distance and a breeze stirring the canopy. Many current theories propose that different indigenous groups left their cities (including the Anasazi [1] cliff dwellers in the U.S southwest) for reasons of environmental degradation: the masses of people could no longer support themselves on the available land. It’s fascinating, maybe also a little discouraging, that we humans are still what we have always been.

It was hard to imagine this vast canopy before me gone, to see the city in stone. There are so many ruins in this area. We started to see it in Tikal in September, and it was everywhere evident on this hike, that anywhere there is a rise in the land, there is a ruin beneath the trees. You see a tree growing with rocks squeezing out between its roots. In the middle of the woods, you’d start a climb and realize there were more rocks beneath your feet than before, that you walked up and over such a uniform bulge. Then we’d see the treasure hunters’ tunnels. In the distance around Flores, the hills look unnatural, and if you ever take a flight from Guate to Tikal or vice versa, you can see that the mounds below you are strangely uniform and steep like no hills pushed from the earth. There is so much here in Guatemala, under the surface. It cannot, and I think it should not, all be uncovered, but it’s really mind boggling to see and yet not see what’s there. These trees protruding from the ruins also brought to mind Tolkein’s Ents. The trees rip up, crumble, and move such carefully cut stone. I think the Ents are a genius characterization of the silent, persistant strength of trees. Carlos informed us that the builders of these ruins used obsidian saws to cut the stone and most of the forest was cut down and burned to procure the lime necessary for construction. It seems the trees are taking their revenge.

On one of the informational signs, we saw a timeline that I’d like to share with you.

- 3114 BC- The beginning of this cycle of the Mayan astrological calendar

- 2000 BC- Corn appears in the region (a BIG deal)

- 300 BC- Most of the ruins we saw were active (Tintal, El Mirador, Nakbé, Wakná)

- 150 AD- El Mirador was abandoned, for whatever reason

- 300 AD- Ruins to the south were active (Tikal and others)

- 600 AD- Ruins at Copán (Honduras) were active

- 900 AD- Most classical Mayan cities abandoned

- 1200 AD- Postclassical Mayan cities active (Mayopan, Zacaleu, Iximché)

- 1500s AD- Spanish show up and ruin everything

- 2012 AD- End of this cycle of the Mayan astrological calendar

This reminded me about this “end of the world” thing. I hear there is some silliness going around about great floods and famines and the earth ripping open and so forth in 2012. However, it’s the Maya who invented the darn calendar, and they know it just means that the wheel is back to the start and will continue turning. It’s like midnight, but for a MUCH bigger wheel.

At present, because of the relatively low traffic flow, the rules of the park are pretty loosey-goosey. What you can and can’t see, what you can and can’t do are often left up to the interpretation of your guide. For example, the previous volunteer group who gave us Pati’s information spent one night camping on top of the temples. We were told that hasn’t been done for 4 or 5 years. There is a tunnel under one of the temples that is full of paintings, and Carlos asked us if we wanted to see it. He told us we’d have to pay 20q each to get in, but he could talk to the man with the keys if we were interested. He also mentioned this had to be a hush-hush thing, so we were not to mention it to other groups and could only do it while if there weren’t other groups in the vicinity. From the beginning, this idea felt like it was just park guards out to make a little extra for themselves. Don’t get me wrong; I would have gladly paid 20q to enter that tunnel and see the paintings, but I get the feeling the official protocol for the tunnel is that it’s reserved for those who come in helicopter and leave hefty donations to continued research. Unfortunately, the man with the keys apparently decided there were too many people about, and we never did get to go in.

Also, upon entering the reserve there are signs saying that no alcohol is permitted in the park. Our first night in El Mirador atop the jaguar temple, there were a few foreign tourists who lit up their cigarettes and began swigging from a gallon size jug of Venado rum (the cheapest and nastiest stuff available). We are not so straight-laced as to completely disapprove; we often fill a Klean Kanteen with red wine for our multi-day hikes as it’s nice to relax around the fire in the evening. We were never told “no alcohol”, we just saw it on signage once in Carmelita; the only reason we didn’t bring any this trip was that we were planning for ridiculously hot weather and therefore concerned with dehydration. Another tour group we spent some time chatting with said their guide told them sleeping atop the temples was no longer allowed because backpackers like their pot and alcohol too much.

As the four of us girls along with Carlos carefully descended the treacherous steps of the Jaguar temple in the early morning light, a group of British boys was running up the steps and one of them cried, “Did we miss sunrise?” He was very disheartened, and his mate muttered, “That’s what happens when your guide spends all night getting stoned.” Tourism is a very tricky thing. Carlos confirmed that many operators spend most of their winnings on drugs and alcohol. Really, I felt some pity for these operators. They’re in charge of all these foreigners who come in, many who don’t speak Spanish with guides who only speak Spanish. They bring in drugs, they bring in alcohol, and they probably think they’re being friendly by offering some to the guides as well, much like we shared our snacks with Carlos. These guides are often young guys and they want to be good guides, they want to get tips. They’re going to try and please and integrate with the groups as much as they can, and eventually they get caught up in acting the wrong part for the wrong group.

One blog we found about the Mirador hike encourages groups to bring in alcohol for the guides instead of monetary tips. “What are they going to do with money in the middle of the jungle?” the author asks. This annoyed all of us. They don’t live in the jungle and barter for food and necessities; they just operate tours there. Carlos, for one, sends his daughters to a boarding school in Guatemala City where they can learn English and German, and come back to help with the tour operation. We were all completely opposed to tipping with alcohol, especially since we work in Guatemala and are painfully aware that alcoholism is the number one killer of the Guatemalan male. A lot of tourists and expats all over the world have this attitude that they can do whatever they please in these parts. And you know what? For the most part they can. No one is going to stop them. That doesn’t mean they should. I love to travel, I love these kind of trips, but all this felt like a cautionary tale about the dark side of tourism. Be mindful fellow travels, if not for your sake, then for your hosts.

On Friday as we got closer and closer to Carmelita, we were all excited to say we finished, to get real showers, to eat heaping plates of fresh food. But once we were back at the campground, packing up our bags and loading the van that we’d hired to pick us up, it was a little sad to say goodbye to Carlos and Maribel, and sad to think how many hours of travel still lay ahead of us. We doled out our tips, our thanks, our hugs, and then piled into the van to begin the lengthy stretch of dirt road back to Flores. We all fell silent, from exhaustion, from a week of talking to each other, from the van’s vibrations being too loud to compete with. I felt in my sleepy daze a sense of satisfaction of a vacation well executed, with the perfect mix of pleasant company, challenge, relaxation, and revelations of new things. The challenge now would be to get back to work and make these last three months count for something.

1. “Anasazi” as a term is under some debate; that is what the current inhabitants called the original people of Mesa Verde when first asked by archaeologists, but it has since come to light that the word literally translates to “ancient enemy”, which is pretty pejorative. We don’t know what the current politically-correct name is.