We just spent two days visiting our friend Charlotte. We like to visit her, but this time it was for business. You see, Charlotte’s program is Municipal Development, which means she’s really good at things like creating women’s groups, organizing people for political action, and working to enhance services provided by local governments. She’s not very construction oriented, though, so when she got a grant to build latrines in a rural village in her municipality, she called us for help.

We just spent two days visiting our friend Charlotte. We like to visit her, but this time it was for business. You see, Charlotte’s program is Municipal Development, which means she’s really good at things like creating women’s groups, organizing people for political action, and working to enhance services provided by local governments. She’s not very construction oriented, though, so when she got a grant to build latrines in a rural village in her municipality, she called us for help.

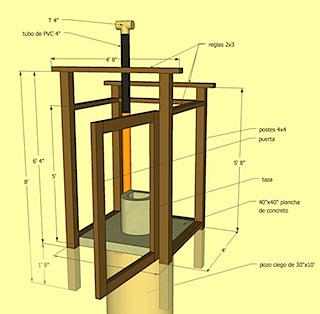

There are two basic types of latrines in use here: letrinas aboneras, or composting latrines; and pozos ciegos, or sanitary pit latrines. The composting latrines are generally better: they last indefinitely, protect groundwater, and you get some fertilizer out of them every year as a bonus- though they are a bit more expensive. The pit latrines aren’t quite as nice, but are WAY better than nothing and they seal the pit so that flies and rodents can’t spread diseases. On the down side, they fill up every five years or so and have to be moved, and can contaminate groundwater if the geologic coditions are wrong. Unfortunately, they are the local favorite in many areas because of their low cost, ease of maintenance, and most importantly, the people are just accustomed to them. After talking with the village, Charlotte found that they really wanted the sanitary pit, despite the good reasons to go with composting… and as we see time and time again, if you give someone something they don’t want, they abandon it. We went with the traditional.

There are two basic types of latrines in use here: letrinas aboneras, or composting latrines; and pozos ciegos, or sanitary pit latrines. The composting latrines are generally better: they last indefinitely, protect groundwater, and you get some fertilizer out of them every year as a bonus- though they are a bit more expensive. The pit latrines aren’t quite as nice, but are WAY better than nothing and they seal the pit so that flies and rodents can’t spread diseases. On the down side, they fill up every five years or so and have to be moved, and can contaminate groundwater if the geologic coditions are wrong. Unfortunately, they are the local favorite in many areas because of their low cost, ease of maintenance, and most importantly, the people are just accustomed to them. After talking with the village, Charlotte found that they really wanted the sanitary pit, despite the good reasons to go with composting… and as we see time and time again, if you give someone something they don’t want, they abandon it. We went with the traditional.

Her town has many Ladino (spanish-speaking) city dwellers, but most of their outlying villages are rural Mayan. Unlike the Q’anjob’al we live and work with, these are from the Mam ethnic group. Their dress is a little different, and their language is VERY different. It’s strange to be surrounded by Mayans jabbering away and not understand a word of it. Some things were the same, though: their friendliness, the communal way they work together, the kids smiling and giggling, and the babies screaming in terror at the sight of white people.

We piled into the back of a pickup at 6am to travel with the teachers headed up the mountain to the village. It was a beautiful, half-hour climb up a steep 4×4 trail to a verdant vallley near the top of the mountains. When we arrived, the villagers were waiting in the schoolyard; only one truck a day comes up there, and they’d heard it long before we arrived.

Charlotte had done her homework, and most of the materials we’d planned out had already arrived: precut wood, sheets of corrugated steel, PVC tubing. Over the course of the next few days, we divided up all the materials amongst the 41 participating families. The extent of the careful planning reflects in part on Charlotte’s good organizational skills, but also on the Mayan preoccupation with everyone getting their fair share. This is important in a culture that is both communal and VERY poor; they even counted out how many nails each family would get: 25 three-inchers, and 50 roofing nails.

One of the most exciting challenges was getting the materials from the staging point in the schoolyard to the individual houses scattered across the mountainside. They do this the way they do everything else here: by mecapál. This is a headstrap that ties to a rope that goes around whatever you’re carrying. Across hill and dale, through mountainside cronfield, down steep ravines, until you come to the adobe hut perched precariously a thousand feet above the valley floor.

The construction went really well. Most rural families have great do-it-yourself skills, and I was able to stand out of the way most of the time. I am a hand-on guy and love to build things, so this is sometimes a challange for me. 🙂 In a way, our presence was largely ceremonial, an endorsement of the validity of the project; their presence was a sort of thank-you for helping connect them with the resources they need to make things in their village a little better. We built one latrine one each of the days we were there, and I am confident that they will have no trouble doing the rest of them themselves (which is really the point of the exercise, anyway). We’ll know for sure when Charlotte goes and does the evaluation sometime next month.

And now, much like last week, here is a play-by-play of how to build a sanitary latrine.

And that was our latrine adventure. In the next few weeks, the village will continue to build the remaining units, and towards the end of the month Charlotte will return to the site to evaluate the final installations for conformance with the projects specifications, as well as give some additional training and answer any questions the villagers might have. And us? We’re off to the South, to attend a bunch of work-related conferences. More on that in coming posts.