WARNING: this post contains images that may be disturbing to some. If you are squeamish about images of medical procedures, you may want to skip this post. Likewise, if you are one of my friends that uses this blog as an educational took for your children, you may wish to review it alone first so you can better explain what’s going on.

As you might have noticed, I didn’t post last week. That’s because I was translating at another jornada medica, or medical mission. Emily and I tried one way back in February, and had a really positive experience. Unfortunately, because of a scheduling conflict with a Peace Corps training event, we were only able to participate for one day. This time, however, I stayed for the whole week.

When I say “it’s like crack for PCVs”, I am talking about instant gratification. Normally, Peace Corps Volunteers work like crazy for two years, and rarely see any results. We are trying to change perceptions, ways of living, attitudes towards the future. These things are glacial in scale: massive, but very slow-moving. It sometimes takes decades to see the results of your work, and that can be demoralizing. At medical jornadas, on the other hand, everything happens in one week. Crowds gather, hernias get fixed, warriors become healers, the blind are made to see, lives are saved. All these things happened this week and more, and we were all part of it. It is a great and humbling experience.

HELPS International is a nonprofit aid organization that brings doctors and equipment to Guatemala for a week to set up field hospitals to arrange free services for needy Guatemalans. This week’s medical team was based out of Bakersfield, California and included dental, surgical, orthopedic, pharmacological, opthamological, gynecological, and general medical care. Some of the doctors speak Spanish, but most need translators. That’s where we come in.

HELPS International is a nonprofit aid organization that brings doctors and equipment to Guatemala for a week to set up field hospitals to arrange free services for needy Guatemalans. This week’s medical team was based out of Bakersfield, California and included dental, surgical, orthopedic, pharmacological, opthamological, gynecological, and general medical care. Some of the doctors speak Spanish, but most need translators. That’s where we come in.

I heard about the jornada a few weeks ago, and emailed Wes, the coordinator, to see if I could bring down one of the ladies from our village. Wes said yes, of course, but also mentioned that their translators had bailed on them at the last minute. I made some calls, and got him three Peace Corps volunteers for the week: Zach, myself, and one other. Emily and I had already decided that only one of us should go, since we had an abnormally full schedule of lectures that week. Since Emily is better at the lectures than I am, I was chosen for the road trip.

While we were communicating with Wes, Emily and I told the two nurses in our village that there would be sophisticated medical services available and to be on the lookout for appropriate candidates. We didn’t want to make a general announcement, so as not to cause a rush: we just wanted the cases that had serious need. The nurses identified two ladies that needed attention for a painful, long-term issue that isn’t easily fixable in Guatemala: a prolapsed uterus. That’s when, after a zillion kids, their uterus is so weak it hangs out of their vagina. The medical team was bringing a gynecological surgeon, and could perform the surgery. Emily went out to formally invite the women.

What followed was a minor disaster: due to rumor and superstition, neither wanted to go. One lady’s kids told her that the white people would sterilize her on the sly if she went, to keep down the Mayans. The other one’s husband must have felt similarly, because he told her that if she went, she should make sure to send him a new wife on her way out of town.

Despite this setback, we decided it was important that I go. Saturday night I packed my bag, turned out the lights, and we settled into bed. At 6am there was a knock a the door. It was Manuel.

Emily was NOT amused, but we opened the door anyway. Turns out, Manuel had spoke at length with one of the husbands (José) and convinced him of the importance of getting his wife medical care. Go Manuel! There was a problem, however. Their welfare check would be coming in this week, and if they were in Huehuetenango at the hospital, they would miss the payout of 300q (about $38). Emily was beside herself… how could a man throw away an expensive surgery to save his wife decades of pain, for a bit of cash-in-hand? The discussion got heated, and Emily eventually had to break out her ace in the hole. To continue receiving their welfare checks, every family needs two monthly signature on their welfare cards. One is from the school principal, attesting that the kids were in school. The other is from the nurses, proving that they were seeing to the health needs of the mother and child. Normally this just means bringing the kids in for vaccinations, but Emily and the nurse had discussed it beforehand: if José didn’t send his wife for the surgery, the nurses were never going to sign the card again. A bit heavy-handed, but it worked: José and Maria were on the bus with me the next day. We arrived at the hospital, I got them a room in the HELPS hostel for patients and family, and I passed out in the bunkhouse for doctors.

Emily was NOT amused, but we opened the door anyway. Turns out, Manuel had spoke at length with one of the husbands (José) and convinced him of the importance of getting his wife medical care. Go Manuel! There was a problem, however. Their welfare check would be coming in this week, and if they were in Huehuetenango at the hospital, they would miss the payout of 300q (about $38). Emily was beside herself… how could a man throw away an expensive surgery to save his wife decades of pain, for a bit of cash-in-hand? The discussion got heated, and Emily eventually had to break out her ace in the hole. To continue receiving their welfare checks, every family needs two monthly signature on their welfare cards. One is from the school principal, attesting that the kids were in school. The other is from the nurses, proving that they were seeing to the health needs of the mother and child. Normally this just means bringing the kids in for vaccinations, but Emily and the nurse had discussed it beforehand: if José didn’t send his wife for the surgery, the nurses were never going to sign the card again. A bit heavy-handed, but it worked: José and Maria were on the bus with me the next day. We arrived at the hospital, I got them a room in the HELPS hostel for patients and family, and I passed out in the bunkhouse for doctors.

Early the next morning as I was staggering to the dining hall, I saw the front gate. It was still about two hours before “opening time”, but there was already quite a throng outside. I went out to take a look. Being white, I walked in and out at will (heh) and what I saw blew me away: a line about two kilometers long, stretching off in to the distance. And look at all the Todos Santeros! Those are the guys with the crazy striped pants; they come from a Mayan town (Todos Santos Cuchumatanes) about three hours away. I took a picture (at the top of the page), and went back to breakfast.

At 8am, things got rolling. The PCVs broke up the work so we could cover as many areas as possible. Zach went to surgery, another volunteer covered dental, and I went to general consultation. General consultation was a lot of fun, but definitely the most work for the translators. You have to get accurate information from a patient that is hard to keep on topic, and oftentimes has pretty sketchy Spanish skills. How do you ask someone what medication allergies they have, if they’ve never even heard of such a thing? Or even been to a doctor before? Likewise, you have to be careful about not asking any questions with implied answers. Everyone is so happy to see a doctor, they answer affirmatively to everything.

At 8am, things got rolling. The PCVs broke up the work so we could cover as many areas as possible. Zach went to surgery, another volunteer covered dental, and I went to general consultation. General consultation was a lot of fun, but definitely the most work for the translators. You have to get accurate information from a patient that is hard to keep on topic, and oftentimes has pretty sketchy Spanish skills. How do you ask someone what medication allergies they have, if they’ve never even heard of such a thing? Or even been to a doctor before? Likewise, you have to be careful about not asking any questions with implied answers. Everyone is so happy to see a doctor, they answer affirmatively to everything.

Me: “Are you allergic to any medication?”

Patient: “Yes.”

Me: “Which ones?”

Patient has a confused look.

Me: “Can you take ANY type of medication?”

Patient: “Yes.”

Aha. This is obviously not going to be a productive line of questioning. I explained to the doctor that they probably don’t have any allergies, and if they did, they certainly wouldn’t know it. We moved onto the next item in the checklist.

Me: “Did the pain start recently?”

Patient: “Yes.”

Then, being suspicious, I asked, “Have you had this pain for a long time.”

Patient: “Yes.”

Um, right. I soon learned to word my questions more carefully, for example:

BAD: Have you had this pain for a long time?

GOOD: How long have you had the pain?

BAD: Do you understand the directions I just told you?

GOOD: Repeat to me the directions I just told you.

They also don’t read, which makes the carefully written directions on the medicine pretty useless. I started drawing a picture of a sun and a moon on bags for anything that gets taken twice a day, and if it’s three times a day, I added a picture of a rising sun. The dosage for some medicines, like Prednisone 5mg, is half a pill a day. I drew a picture of a pill broken in half. Prednisone is a steroid that reduces inflammation and promotes healing, and it’s one of Barry’s favorite medications. We must have given it to half of the patients we saw.

My doctor, Barry, is a kind, amiable, down-to-earth guy. He cares a lot for the patients, but is also realistic about what can be accomplished in this setting. He has a wealth of knowledge, and taught me a lot about diseases and anatomy and so forth in the days I worked with him. He patiently explained everything to me in detail, not just so I could effectively explain to patients what was going on, but also to help me learn. And man, did we see a lot of weird stuff! The first day was a lot of hernias, some of which were quite large. One man’s scrotum was bigger than a softball, because it was filled with his intestines. Ouch.  We also saw some pretty depressing cases, like the lady who brought in her 2-year old with cerebral palsy. Cute, smiley kid… but nothing going on upstairs. It was heartbreaking, and we had to refer her elsewhere. That was the hardest part of the week, when I had to explain to someone that their kid would probably never walk or talk. Same with the poor 21-year-old girl with cancer in her arm. It looked like she had somehow wedged a football and a softball between her radial and ulner bones, and they told her she would need to see an oncologist at the state hospital. If she’s REALLY lucky, she will only lose her arm at the shoulder. The bummer is that a lot of cases were far more progressed than they should have been, due to lack of available medical care in Guatemala. They should have been caught earlier. If prevention isn’t a good reason for universal healthcare, I don’t know what is.

We also saw some pretty depressing cases, like the lady who brought in her 2-year old with cerebral palsy. Cute, smiley kid… but nothing going on upstairs. It was heartbreaking, and we had to refer her elsewhere. That was the hardest part of the week, when I had to explain to someone that their kid would probably never walk or talk. Same with the poor 21-year-old girl with cancer in her arm. It looked like she had somehow wedged a football and a softball between her radial and ulner bones, and they told her she would need to see an oncologist at the state hospital. If she’s REALLY lucky, she will only lose her arm at the shoulder. The bummer is that a lot of cases were far more progressed than they should have been, due to lack of available medical care in Guatemala. They should have been caught earlier. If prevention isn’t a good reason for universal healthcare, I don’t know what is.

Here is a 14-year old girl with her year-old baby. She did the proactive thing any good mother would do, and brought her kid in for an exam. He had a staph infection on his face, and we gave her some medicine and sent her on her way. That’s an example of GOOD medical service, dealing with the problem before it gets to be expensive and complicated to cure. I am certain that she would not have brought her kid in if she had to pay a heap of money for the private doctors. She had no money to pay.

Here is a 14-year old girl with her year-old baby. She did the proactive thing any good mother would do, and brought her kid in for an exam. He had a staph infection on his face, and we gave her some medicine and sent her on her way. That’s an example of GOOD medical service, dealing with the problem before it gets to be expensive and complicated to cure. I am certain that she would not have brought her kid in if she had to pay a heap of money for the private doctors. She had no money to pay.

A few minutes later, we saw this kid with a double cleft palate. Barry smiled and tickled the kid as he did the exam. What a happy baby, but what a serious problem. Barry called in the surgeon, who told us that the medical team this week was only set up to do single cleft palates, but the team in January would be bringing a well-known plastic surgeon that specializes in doubles. We wrote a referral slip, Barry made some dietary and care recommendations to the mother, and off they went.

A few minutes later, we saw this kid with a double cleft palate. Barry smiled and tickled the kid as he did the exam. What a happy baby, but what a serious problem. Barry called in the surgeon, who told us that the medical team this week was only set up to do single cleft palates, but the team in January would be bringing a well-known plastic surgeon that specializes in doubles. We wrote a referral slip, Barry made some dietary and care recommendations to the mother, and off they went.

We also saw a lot of people with bladder infections. The nurses were all running around like chickens with their heads cut off, trying to help everyone, so I asked Barry if I could do the urine tests to save time. “Sure,” he smiled, so they showed me how to use the indicator strips to test of proteins, sugar, hemoglobin, pH, leucocytes, and other stuff. Modern medicine is amazing! You get all that information from one disposable strip.

The last patient we saw the first day was yet another lady with a hernia. Everyone here lifts 100-pound grain sacks all their lives, so this is a common problem. As I was explaining the surgery to her, she asked me, “While you’re in there, can you also tie my tubes? I’m tired of having kids.” Well, they aren’t really in the same place, but I asked Barry anyways.

“We’re not doing those this week,” he said. “But HELPS won’t do it anyways, if her husband isn’t here to sign the papers.”

Excuse me? I was taken aback, and had to have him clarify that for me. You mean that if a woman wants something done to her own body, her HUSBAND gets to decide? What is she, a pet? An animal? That policy is further reinforcing the oppressive machismo system that is already in place here. And I bet that if the husband wants a vasectomy, he doesn’t have to get the woman’s permission.

“Well, I don’t know about that,” he shrugged. “Doesn’t matter, men here won’t do it anyways.”

That actually isn’t completely true. ALAS, the agency Emily was working with a few weeks ago, specializes in providing low-cost vasectomies and they even have a “vasectomy guy” that gives educational lectures to men and promotes the surgery. It’s slow business, but understanding is increasing.

The truth is, Guatemala actually has a LAW that says a woman has the right to decide her own reproductive destiny. But as we talked some more, and Barry explained to me the tricky political position that HELPS is in. If word gets out that they participated in sterilizing a person without the spouse’s consent, they would never get invited back to work in a region or village. The needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few; a woman enslaved to her husband is the price to pay for being allowed to provide hundreds of others with lifesaving medical care.

After two days, the PCVs got together and decided to switch it up, so we could see everything. I had become buddies with the dentists during the off hours, so I wanted to hang out with them. “I’ll warn you, dental is pretty serious,” the other translator told me. He was right: those guys are the hardest working guys in showbusiness. I saw more blood and guts in my one day there than in all the rest of the hospital put together… INCLUDING the four operating tables. We started off easy, and as the patients started filling the waiting room chairs, I helped Jeff load the syringes with Lidocaine.

After two days, the PCVs got together and decided to switch it up, so we could see everything. I had become buddies with the dentists during the off hours, so I wanted to hang out with them. “I’ll warn you, dental is pretty serious,” the other translator told me. He was right: those guys are the hardest working guys in showbusiness. I saw more blood and guts in my one day there than in all the rest of the hospital put together… INCLUDING the four operating tables. We started off easy, and as the patients started filling the waiting room chairs, I helped Jeff load the syringes with Lidocaine.

Our very first case of the day was pretty hard-core. It was an old lady, with GNARLY teeth, yellow and pointing in odd directions, pocked full of black holes. About half of her teeth were gone. No, wait, they’re still there… they are just broken off at the gumline, rotten black pits of reeking goo.

Our very first case of the day was pretty hard-core. It was an old lady, with GNARLY teeth, yellow and pointing in odd directions, pocked full of black holes. About half of her teeth were gone. No, wait, they’re still there… they are just broken off at the gumline, rotten black pits of reeking goo.

Never daunted, the guys launched right in. Tom carefully numbed her up and pulled a few of the flimsiest teeth. Then he switched out with Chip, the oral surgeon. Those two guys are long-time buddies, and make an excellent team. Chip got busy with the scalpel, splitting the lady’s gums all the way around the ridge of her mouth. Before my disbelieving eyes, he peeled them back, revealing the skull where the rotten nubs of teeth were embedded. Using a tool that looks suspiciously like a screwdriver, he started prying out teeth, broken roots, you name it. I was mesmerized.

“Light. LIGHT!” Jeff barked, as the flashlight I was holding drifted off target.

A few of the stubborn ones required a hammer (seriously), then Chip yelled, “bone file” and held out his hand.

“Are you kidding?” I asked him. He then explained that if you don’t file down the bone ridges at the edge of all those sockets, then when the gums heal up over the bone, they will be forever cutting the gums from the inside. The crunching sound make me a little queasy and he rubbed the bone chisel around, in much the same way one might move a toothbrush around… if they were brushing a grisly, bloody bone ridge instead of their pearly whites.

“Are you kidding?” I asked him. He then explained that if you don’t file down the bone ridges at the edge of all those sockets, then when the gums heal up over the bone, they will be forever cutting the gums from the inside. The crunching sound make me a little queasy and he rubbed the bone chisel around, in much the same way one might move a toothbrush around… if they were brushing a grisly, bloody bone ridge instead of their pearly whites.

He then moved onto the lower jaw, and did the same. “The lower jaw bone is like a rock,” he said. “The upper is easier, skull is a lot softer.” He pulled the entire flap of her gums back, revealing the bone. The suction still wasn’t working right, and the blood welled up, making her gums slippery. It flipped off of the dental pick, smacking against the bone and splattering blood onto the faces of Tom, Chip… and me. Yech. There was even a big streak of blood on the floor.

He then moved onto the lower jaw, and did the same. “The lower jaw bone is like a rock,” he said. “The upper is easier, skull is a lot softer.” He pulled the entire flap of her gums back, revealing the bone. The suction still wasn’t working right, and the blood welled up, making her gums slippery. It flipped off of the dental pick, smacking against the bone and splattering blood onto the faces of Tom, Chip… and me. Yech. There was even a big streak of blood on the floor.

“OK, let’s sew this up” he said as he took out the last nub. About 60 stitches later, they lady was staggering out of the office, toothless but on the way to being a LOT healthier. This is when I do my part, explaining the post-op care. After she leaves, I give the “you better brush your teeth or else you’ll end up like her” speech to everyone else in the waiting room. Many people don’t realize this, but having rotten teeth in your head leads to a host of systemic illnesses. When cavities reach the interior pulp of the tooth, the infections have direct access to the bloodstream, and can accumulate elsewhere, causing brain or heart problems, arthritis, or who-knows-what. Here we see Tom and Chip passed out in the lawn after lunch: indeed, the hardest working guys in showbusiness.

“OK, let’s sew this up” he said as he took out the last nub. About 60 stitches later, they lady was staggering out of the office, toothless but on the way to being a LOT healthier. This is when I do my part, explaining the post-op care. After she leaves, I give the “you better brush your teeth or else you’ll end up like her” speech to everyone else in the waiting room. Many people don’t realize this, but having rotten teeth in your head leads to a host of systemic illnesses. When cavities reach the interior pulp of the tooth, the infections have direct access to the bloodstream, and can accumulate elsewhere, causing brain or heart problems, arthritis, or who-knows-what. Here we see Tom and Chip passed out in the lawn after lunch: indeed, the hardest working guys in showbusiness.

The last day, I had the pleasure of working with the dentists one more time. We were chatting about their office in Bakersfield, about flying airplanes (a favorite topic for me and any other pilot), and the trials and tribulations of the dentistry business. They invited me to visit them in California when I was done with Peace Corps, and I fully intend to do so. We were interrupted by a sickening crunch behind me. “Time to call in the relief pitcher,” Tom said, pouting as he sat down. He just broke off another tooth. “All those other doctors don’t realize it, but this is serious business. It’s like trying to get a Pepsi bottle out of hardened concrete.” Chip flipped down his opticals and opened another scalpel packet.

The last day, I had the pleasure of working with the dentists one more time. We were chatting about their office in Bakersfield, about flying airplanes (a favorite topic for me and any other pilot), and the trials and tribulations of the dentistry business. They invited me to visit them in California when I was done with Peace Corps, and I fully intend to do so. We were interrupted by a sickening crunch behind me. “Time to call in the relief pitcher,” Tom said, pouting as he sat down. He just broke off another tooth. “All those other doctors don’t realize it, but this is serious business. It’s like trying to get a Pepsi bottle out of hardened concrete.” Chip flipped down his opticals and opened another scalpel packet.

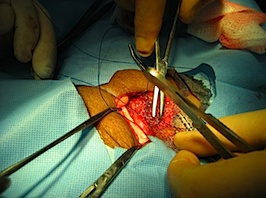

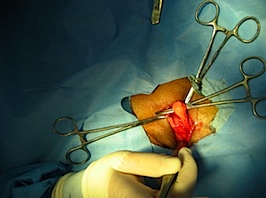

At one point, I got to try translating for general surgery. It turned out to be the easiest of the stations, so I only did it for a half day: long enough to see the creepy stuff but not get bored with it. They were running both local and general anesthesia tables, and I spent much of my time at the former. Sleeping patients don’t talk much. But I did get to talk to the anesthesiologists a bit, and they were interesting characters. “It’s like flying a plane,” one said, tweaking a dial. “Right now, I am in cruise flight. Just watching the instruments. When they go to sleep, its like takeoff. When I wake them up, it’s like landing. Easy.” Yeah, easy. I found out later he is a pilot as well, with a pretty amazing story of surviving a crash that left several bones broken and avgas burns on 90% of his body.

At one point, I got to try translating for general surgery. It turned out to be the easiest of the stations, so I only did it for a half day: long enough to see the creepy stuff but not get bored with it. They were running both local and general anesthesia tables, and I spent much of my time at the former. Sleeping patients don’t talk much. But I did get to talk to the anesthesiologists a bit, and they were interesting characters. “It’s like flying a plane,” one said, tweaking a dial. “Right now, I am in cruise flight. Just watching the instruments. When they go to sleep, its like takeoff. When I wake them up, it’s like landing. Easy.” Yeah, easy. I found out later he is a pilot as well, with a pretty amazing story of surviving a crash that left several bones broken and avgas burns on 90% of his body.

At the local anesthesia table, there was more for a translator to do: check to see if the patient was ok, or in the case of the younger ones, keep their attention with conversation. I saw a hernia operation (there’s a plastic mesh they use to patch the hole in the abdominal musculature). The exceedingly friendly Dr. Imler gave me an anatomy lesson as we went, pulling out various tubes and fatty masses to show me. “That’s the vas deferens,” he said, pulling it out and holding it to the side with some foreceps. “We don’t want to cut that!” I leaned over to get a better look, and touched the blue drape. He quickly reminded me that I am not allowed to touch anything blue (and therefore sterile). At the next table, the orthopedic surgeon was taking a bony mass off of a boy’s finger. The day before, he had borrowed a pair of wire cutters from one of the maintenance guys, sterilized it, and use that to supplement his scalpel. The conditions here require resourcefulness.

The doctors were all very professional, though I did see some funny stuff you aren’t likely to expect. Here’s the instrument table right before one of the surgeries. Man, on TV they are always laid out so neatly. Also, I got in early when they were preparing for the day. Linkin Park was blaring on the radio as they set up their sterile environment. “I have to have my music”, Dr. Imler shouted over the din. By the time he was cutting, though, it had been changed to softer fare.

The doctors were all very professional, though I did see some funny stuff you aren’t likely to expect. Here’s the instrument table right before one of the surgeries. Man, on TV they are always laid out so neatly. Also, I got in early when they were preparing for the day. Linkin Park was blaring on the radio as they set up their sterile environment. “I have to have my music”, Dr. Imler shouted over the din. By the time he was cutting, though, it had been changed to softer fare.

Every night after dinner, there was some sort of talk or presentation. Thursday night was a sort of “open mic night” for people to tell personal stories or anecdotes. Much of the tales were religious testimonials- not something I am particularly interested in. The other PCVs, however, were egging me on to talk about the local history of Huehuetenango. This seemed appropriate to me, as I’d been in some discussions on the topic at various points throughout the week, and all of the doctors were interested in learning more about the people they were helping.

So, I got up and told a story. First I thanked everyone for coming to Huehuetenango, since so much aid seems to go to the “popular” places like Sololá and Antigua. To come all the way out here is a challenge, and I respect those who do it. I also wanted them to know more about the present-day Mayans, since we don’t learn much about them in the U.S., and a lot of the doctors had been asking about the “softball team,” as they called the Todos Santeros with their uniform of striped pants and shirts. The crowd nodded, approving the idea of a brief history lecture.

The story won’t appear here, as it was a very personal account and I had to fight back tears towards the end (1). But after the story was over, so many people came up to me and thanked me for sharing it, and giving them a more realistic perspective on the present-day Mayan condition. I am glad to have shared it, and I left them each with a challenge: do not stop serving these people when you leave Guatemala. Spread the word about what has happened to them, what continues to happen to them. Tell friends and neighbors. Let America and the world know.

Throughout the week, I would bump into José and Maria (from my village) as they made their way through the system. After they had their initial consult, I spoke to the gynecologist about Maria’s condition. In the US, of course, HIPA would prevent that sort of thing, but this is a third world country and “health privacy” is a relatively unknown concept. That is a benefit in this case, because oftentimes the rural folk don’t really understand the specifics of what they’re being told, and if I get accurate information I can relay it to the local nurse in our village to make sure they get the proper follow up care. It turns out Maria did not actually have a prolapsed uterus; rather, it was her bladder prolapsing. The continuous bleeding was due to a nonviable pregnancy that would not miscarry.

Towards the end of the week, I saw Maria in recovery. I translated for the gyno surgeon, again to make sure I had accurate information. She explained to Maria that they had lifted her bladder and sewed it in place, then they simply “cleaned” her uterus. Maria and Jose were greatly relieved; they asked twice to make sure they could still have children. I guess six isn’t enough.

“Well, tell her if she ever DOES decide to get her tubes tied, she should come back and get a total hysterectomy instead,” the surgeon explained. “In a few years, she WILL have a prolapsed uterus, and it’s faster, safer, and less painful to have that taken out before it hangs out all the way down to her knees.”

Rumor runs rampant here, and I need to know the truth about these things to make sure that Emily and I aren’t put in a compromising position. What danger could come from not knowing the specifics of her surgery, you ask? Well, earlier that day, José came up to me and asked for help.

“Can you read this to someone I have on the phone?” he asked, holding up his cellular.

I was confused, then he explained that since they couldn’t get home in time go get their welfare check, he had asked one of the doctors to write a note explaining that they were in the hospital. Like many of our villagers, José can’t read, so he wanted me to do it for him. I quickly scanned the note, then I choked.

“José, tell them we’ll call back.” Then I went to find Dr. Sanchez, who’d written the note. He’s a young, friendly Guatemalan doctor who was helping with the medical team.

“Is this true?” I asked. “It says here that Maria had a total hysterectomy.”

He looked confused. “How would I know? I just wrote what José told me to write.”

Aha. There was a BIG misunderstanding somewhere. I looked at the note in my hand, realizing it could cause decades of medical disaster for hundreds of people, a sort of atom-bomb for Mayans. You see, because of this continuing belief amongst the Mayans that outsiders want to sterilize them, to kill off the Mayan race, it takes a lot of trust for them to show up to these medical missions. If a note got out saying someone had actually been sterilized instead of given the treatment they’d been told, it would cause ongoing fear and speculation, keeping people away from the doctor for another generation at least. These are the kind of misunderstandings we work to prevent. I checked back with the surgeon again, and she reassured me that Maria had NOT had a hysterectomy… then I destroyed the note.

Translating for other aid organizations isn’t really part of our job description as Peace Corps volunteers. In fact, one of the other PCVs was constantly worried he’d get in trouble for ditching his “real” job in the county government office. Luckily, I don’t have to worry about that too much. Basilio, my boss, is rarely mislead by job descriptions and red tape… he puts people first. Also, I gave more charlas (health lectures) this week than the rest of the year put together: during outpatient consultations, I talked about clean drinking water, smoke in the house, disease prevention, proper nutrition. But what are we REALLY here for? According to the Peace Corps’s mission statement, we’re here to provide host countries with needed technical assistance, teach Guatemalans about what kind of people Americans really are, and expose Americans to a bit of Guatemalan culture. I think we did that in spades.

(1) It might even be construed as “political”, so Peace Corps prefers I not post it here. In fact, I have chosen to edit this entire post pretty heavily and it will appear in its entirety when we finish our service next year.